The violin – in all its forms – undoubtably plays a major role in the music of the African continent. Here we present an overview of the stringed instrument, played by those who made it famous in the past, as well as those who celebrate its resonance today.

The Ethiopian masenqo

Much like the krar lyre or the kebero drum, the Ethiopian single-stringed fiddle also known as the masenqo, is the instrument of choice for the Azmaris. These musicians have shaken up Addis Ababa’s nightlife within the city’s popular cabarets, thanks to their eloquent social commentary and their impressive ability to improvise – the two key qualities of a good Azmari. From the Sostu to the Yeweddal (the venue run by famous masenqo player Adanèh Tèka), the cabarets (azmaribet) continue to offer space for collective catharsis, as well as an essential place to visit for anyone that sets foot in Ethiopia. As a result of their collaboration with musicians from the Fendika, a must-see azmaribet run by dancer Melaku Belay on Zewditu Street, The Ex, a Dutch experimental post-punk band, released Lale Guma/Addis Hum in 2015. In this hybrid record, Endris Hassen’s masenqo blends together with The Ex’s abrasive riffs, giving the traditional instrument a slightly more underground feeling than usual.

Of course, the great figures of the “golden years” of Swinging Addis music, have also incorporated the instrument to create infectious grooves, from Getatchew Mekurya to Hailu Mergia. But it’s in Mulatu Astatke’s music that the maseqo takes on a new and psychedelic dimension, especially on Inspiration Information, Volume 3, an album which brought together the aforementioned ethio-jazz pioneer with London-based collective The Heliocentrics (Strut Records, 2009). In “Masenqo”, a track dedicated to the instrument, the masenqo lies between the sounds of a distorted harp and a theremin! The masenqo undoubtedly, lends itself well to experimental approaches, and even mystical ones, as heard on takes with The Pyramids in 1973 after their trip to the footsteps of the Coptic Christians of Lalibela (Northern Ethiopia), in the hands of Idris Ackamoor himself – “It was like playing on a highly spiritual work of art, he recalls. I still have this masenqo hanging on the wall at home; it’s a beautiful, carved object with the Ethiopian cross on it. It’s fretless so it’s your soul that guides your playing.” Today the masenqo is used in producing club music through the fingers of Ethiopian producer Endeguena Mulu, who considers himself “an electronic Azmari”.

Listen: Adanèh Tèka, Mulatu Astatke / The Heliocentrics, Idris Ackamoor & The Pyramids.

The Tuareg imzad

In the Sahara desert, from the stone cathedrals of Tassili to the Adrar des Ifoghas’ massif in Mali, women traditionally craft and play the imzad, the single-stringed fiddle of the Tuareg people, to accompany with their bows, the epic poetry and gallant songs provided by men. “The imzad is to the Tuareg people what the soul is to the body,” claim the members of Imzad, an Algerian band known for its desert blues-rock which, in the footsteps of Tinariwen, have long since adopted the electric guitar to beef up its sound and bring the assouf of the Tamasheq to international stages (“assouf” is the term for the feeling often imperfectly translated as “nostalgia”). Their Gibson guitars allowed the traditional oral culture to continue by gradually replacing the imzad, the ancestral instrument which was already once threatened with extinction, when in the 2000s, you could find only two women who could play it, in Algeria.

So, in order to preserve the soul of the Tuareg culture, the association “Save the Imzad” opened several schools in the Hoggar to ensure the education and practice of the instrument to young Tuareg women, founding a recording studio and workshop, allowing the imzad to be finally recognized as an “intangible cultural heritage of humanity” by UNESCO in 2013. On the road, other nomadic souls have become infatuated with the thousand-year-old sound of the imzad. Damon Albarn, in 2014, stopped off at the Maison des Jeunes [“youth club”] in Bamako with the Africa Express caravan to record an African tribute to “In C”, Terry Riley’s minimalist masterpiece, with seventeen Malian musicians and Brian Eno. The Peul flute, the balafon, percussions, the ngoni, the kora, the melodica and the imzad – here played by Guindo Sala – offer an alternative and equally eccentric energy to the repetitive trance written by the North American composer.

Atlantic violins (Cape Verde; Brazil)

In Cape Verde, the maestro of the violin was called Antonio Travadinha. Now considered one of the key figures of the archipelago’s musical heritage, his talent had remained a secret up until the release of Feiticeira De Cor Morena, the musician’s only studio album, recorded in Lisbon in 1986, at already over forty years old. Born on the island of Sant’Antão, Antonio Travadinha began his career at dances where he absorbed through his violin the traditional repertoire of mornas, coladeiras and other mazurkas. Through this practice, he developed a virtuosity that was matched only by his capacity for improvisation, an overwhelming feat heard on No Hot Club, a live album recorded at Lisbon’s Hot Club, the oldest jazz club in Portugal.

But during its colonial undertaking, Portugal also took the violin to Brazil, in particular to the northeastern state of Pernambuco. There, the stringed instrument often duplicates or replaces the accordion which, along with the triangle and zabumba, constitutes the signature sound of forró music – as heard from João do Vale. More recently, Siba made a name for himself in Recife as a specialist of the rabeca (a rustic violin), with the band Mestre Ambrosio. They appeared in the middle of the Mangue Beat wave, a musical protest movement initiated in the 1990s, fusing modern music (rap, funk, reggae, punk and electronic) with Nordeste folklores (maracatu, frevo, coco, ciranda). In 2002, Siba settled down amongst the sugarcane fields of Nazaré da Mata, where everything lives by the pulse of the maracatu de baque solto [the “rural” form of the maracatu; translator’s note], and recorded Fuloresta Do Samba with local musicians – take a listen to the superb “Maria, Minha Maria”. In fact, this region is full of excellent violinists like Mestre Salustiano or Mestre Luiz Paixão, a true icon who was recently featured in the electronic compositions of Sociedade Recreativa, the latter formed by the meeting of the Franco-Brazilian trio Forró de Rebeca and the Brazilian-American producer Maga Bo.

Listen: Antonio Travadinha, Siba, Sociedade Recreativa.

The so-kou from Mali

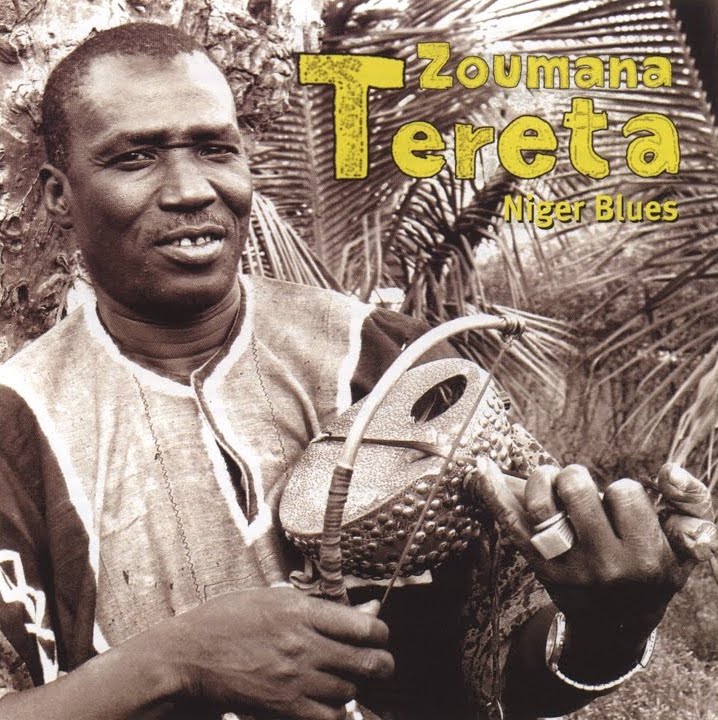

The Mandingo region boasts many single-string violins: the riti from the Fulani shepherds – fully hypnotizing in the hands of Gambian griot Juldeh Camara who teamed up with Justin Adams on In Trance – the ruudga from the Mossi in Burkina Faso… In Mali, the instrument is called so-kou and it is the virtuous Zoumana Tereta (a truck driver no less) who made it famous throughout West Africa. A hobby that would soon fast-track him to the Badema National and the Instrumental Ensemble of Mali, allowing him to perform alongside Oumou Sangaré, Bassekou Kouyaté and Samba Touré. The latter paying him a beautiful tribute on “Tribute to Zoumana Tereta” as the closing track of Wande, stretching a ghostly sample from the great master. During his career, Zoumana Tereta published two solo records: Niger Blues in 2003 and Sokou Fola in 2008. But as a man of his time, he also became established in the hip-hop scene, lending his so-kou to Malian rap pioneer Zion B on “Ségou”, and again to Mokobé on “Safari” in 2007, when the rapper from Vitry-sur-Seine [a suburb city South of Paris; translator’s note] made a return to his Malian roots with the album Mon Afrique.

When the war in Mali broke out in 2012, many voices spoke up about its disastrous consequences for the civilian population. This was the case for various Malian artists, but also for European groups such as Dirtmusic, whose members fell in love with the country during a visit to the Festival Au Désert. After the record BKO, conceived with Tamikrest in 2010, Dirtmusic returned to Mali to record Troubles (Glitterbeat, 2014), an album that invites Samba Touré and Zoumana Tereta on the so-kou violin, and the result is a rock and digital magma that perfectly illustrates the highly tense conflict occurring at that time. Last but not least, we have the recent collaboration from French artist Manjul in Dub To Mali Season 3: Douba (Baco Records, 2019). Recorded in the Bamako-based backyard of the afro-dub pioneer, the record showcases a mix of Mandingo traditional sounds, dub and lusciously reverb-drenched so-kou.

Of course, Mali has also had its share of “classical” violinists and they themselves had truly extraordinary destinies! Invited to study music in Cuba in 1964 through an exchange program between “socialist” African countries and the Cuban government, ten Malian musicians – including violinists Aliou Traoré and Moustapha Sako – created the charanga orchestra Las Maravillas de Mali, and recorded a cult album in 1968. When they were forced to return home in 1971, the musicians brought back with them cha-cha-cha, guarachas, son montuno, boleros and salsas, making a deep impression on Malian artists and the whole Malian scene with Afro-Cuban hits such as “Africa Mia”, “Lumumba” and “Chez Fatimata”.

Listen: Zoumana Tereta, Dirtmusic, Manjul, Maravillas de Mali.

Maghreb violins

Over the centuries, the violin has been adopted by various Maghreb countries, directly descending from the Persian kamancheh. In Moroccan popular music in particular, the violin is often played sitting and upright. It has gradually replaced the rebâb – the Berber spiked fiddle – which Aziz Ozouss admirably transported into modern and even psychedelic territory where the instrument intensifies the gnawa trance of Bab L’Bluz on Nayda! (Real World, 2020).

In Tunisia, Ridha Kalaï remains one of the most famous violinists in the country, renowned for the extreme sensitivity of his playing style, his romanticism, but also for having composed most of diva singer Oulaya’s repertoire from the early 1950s. But it is another Tunisian instrumentalist, Sousse-born Jasser Haj Youssef, who shines today on an international level, solo, or alongside artists such as Khalile Chahine, Piers Faccini or Ibrahim Maalouf. Recognized for his impressive technique, his musicality and his deep musical heritage, the violinist also shows great originality in that he is the first to have rediscovered a baroque instrument called the viola d’amore. His first album, Sira, brilliantly demonstrates his fascination with the similarities that exist between traditional Arab music, jazz music, Western and Indian classical music, with personal nods to Bach and Coltrane.

Listen: Aziz Ozouss de Bab L’Bluz, Ridha Kalaï, Jasser Haj Youssef.

Egypt, in the footsteps of Abdo Dagher

“Abdo Dagher is a true living legend. Born in 1936, he is the greatest violinist of classical Egyptian music; he has played with Oum Kalthoum, Mohamed Abd Al Wahab… He is a master in the art of taqseem, the traditional Arabic improvisation practice,” wrote flutist Naïssam Jalal in the booklet of Om Al Aagayeb (Les Couleurs du Son, 2019). “Abdo Dagher welcomed generations of young musicians into his living room and trained us without ever asking for anything in return. Abdo’s sound penetrated my soul in an indescribable way. Later when I left his apartment, the hallucination began. His violin kept playing in my ears, and I could hear the phrases, the long notes, the detail of the hair on the strings. Abdo’s sound had possessed me.” As a way of paying tribute to him, Naissam Jalal shares space with Abdo Dagher on “Am Abdo” as part of an album recorded in Cairo. The record transcribes in music the memories of the three colorful years she spent there.

Luthier, composer, virtuoso and teacher Abdo Dagher took part in many recordings throughout his immense career, including Mozart in Egypt in 2005, an unclassifiable work where you can hear Mozart on a ⅞ rhythm on which is laid an improvised dhikr a few bars before the requiem. Specialist of unexpected crossovers, Abdo Dagher can also be found with the Japanese collective J.A.K.A.M. in 2015: on “Earth Dance”, the great master placed himself at the service of a universalist deep house offering, crossing bows with a tonkori zither (Japan), a gamelan (Indonesia), gnaoua qraqeb (Morocco) as well as a ney flute (Middle East)!

Over the past ten years, Cairo’s experimental scene has become a creative platform for the avant-garde. Of its pillars is Maurice Louca, a musician who started out as a solo artist during the Arab Spring before forming a proper band consisting of oud, vibraphone, saxophone, guitar, piano and percussions… his third album Elephantine is a true whirlwind of cosmic and minimalist jazz in the style of Egypt-era Sun Ra. In particular on the track “The Palm of a Ghost”, with Ayman Asfour on violin, Maurice Louca adorned the classical sounds of Egyptian music with magnificent electronic and spectral textures.

Listen: Abdo Dagher; Naïssam Jalal in collaboration with Abdo Dagher and a tribute to the master; Maurice Louca.

Jamaica: mento violin… or reggae!

The lesser-known ancestor of reggae and close cousin to Trindad’s calypso, mento had remained the true popular music in Jamaica until the 1960s. This music would be heard at the end of every day, played by the farmers and laborers of the island’s rural areas. Rhumba box, piano, maracas, banjo, double bass, and bamboo clarinet or saxophone made up the mento instrumentarium, sometimes completed by the violin, a homemade instrument also made of bamboo or hemp – as well as the strings and a bow, which had to be lubricated with water or saliva in order to produce a decent sound! One of the most famous mento violinists was Theodore Miller, a Jamaican man who rose to popularity in the 1960s with the Lititz Mento Band before local music was permanently eclipsed by reggae. Thankfully, the genre was later rediscovered at the beginning of the 2000s.

If mento is a genre that has dramatically inspired reggae, then what is the role of violin in these riddims? It is a rather rare feature, but you can find a few examples! Among the most remarkable, and still based in Jamaica, are the Twinkle Brothers, the band formed by three brothers in 1962 in the ghettos of Falmouth. Achieving fame from 1975 with the album Rasta Pon Top, the Twinkle Brothers flew to Warsaw, Poland for a European tour, where they recorded Higher Heights – Twinkle Inna Polish Stylee with the Polish ensemble Trebunie-Tutki: roots reggae and folkloric music from the mountains, a truly surprising mix! And this would not be the last time Trebunie-Tutki’s violins would be featured amongst the Twinkle Brothers’ repertoire: the odd ensemble repeated the experience in a more rootsy way on Dub With Strings and Don’t Forget Africa in 1992.

The Twinkle Brothers and the Polish group Trebunie Tutki, also appeared on the bill of the Ostróda Reggae Festival in 2018, for the 25th anniversary of the release of the album Higher Heights.

Meanwhile in London, in a tense social environment marked by racism and police violence against West Indian communities, Jamaican poet Linton Kwesi Johnson developed a new form of expression between music and poetry, labeled “dub poetry”. He would become the spokesman in the battle for recognition of Black people within British society. His dub poetry was substantially politically charged and it frequently met with the violin of Johnny Taylor, member of the Reggae Philharmonic Orchestra, as heard in the 1991 album Tings an’ Times and in the last two volumes of LKJ in Dub, the stringed instrument adding strength to the power of the singer’s lyrics.

Listen: Jamaica – Mento 1951 – 1958 (Frémeaux), Théodore Miller, Twinkle Brothers et Linton Kwesi Johnson.